Investing in bonds is one of those things often proposed by banks to the average saver. In fact, not everyone knows that the global bond market is larger than the stock market. The former is estimated to be around $133 trillion, including sovereign debt, corporate debt, and other debt instruments. On the other hand, the stock market is estimated to be around $95 trillion, including all publicly traded stocks worldwide.

In the article titled The Accumulation Phase: The Mountain to Climb, we looked at the main asset classes and attempted to define each one.

What is a Bond?

In simple terms, a bond is a security that gives the investor who buys it the right to receive the repayment of the amount paid at maturity, along with interest as remuneration.

It’s time to take a further step and try to understand how this important financial instrument works, which almost every investor has in their investment portfolio.

As is often the case in finance, things are not always as they seem. The functioning of a bond is counterintuitive

When interest rates rise, bond prices fall, while when interest rates fall, bond prices rise. The relationship is inversely proportional

To clarify the concept, let’s take the simplest example: a Zero-Coupon Bond.

P = 100 / (1 + i) ^ t

Where:

- P is the price you should pay today to receive 100 in t years;

- t is the time;

- i is the interest rate.

From a mathematical perspective, the interest rate is in the denominator of the formula used to calculate the bond price, which explains the inverse relationship between the two variables.

From an economic perspective, new bonds become more attractive. When interest rates rise, they will offer higher yields compared to existing bonds. Conversely, existing bonds will be less attractive because they pay a lower interest rate. Investors can achieve better returns with new issues.

Ultimately, the price of the bond, like all goods and services, will be determined by market supply and demand dynamics.

Why I Choose Not to Invest in Bonds

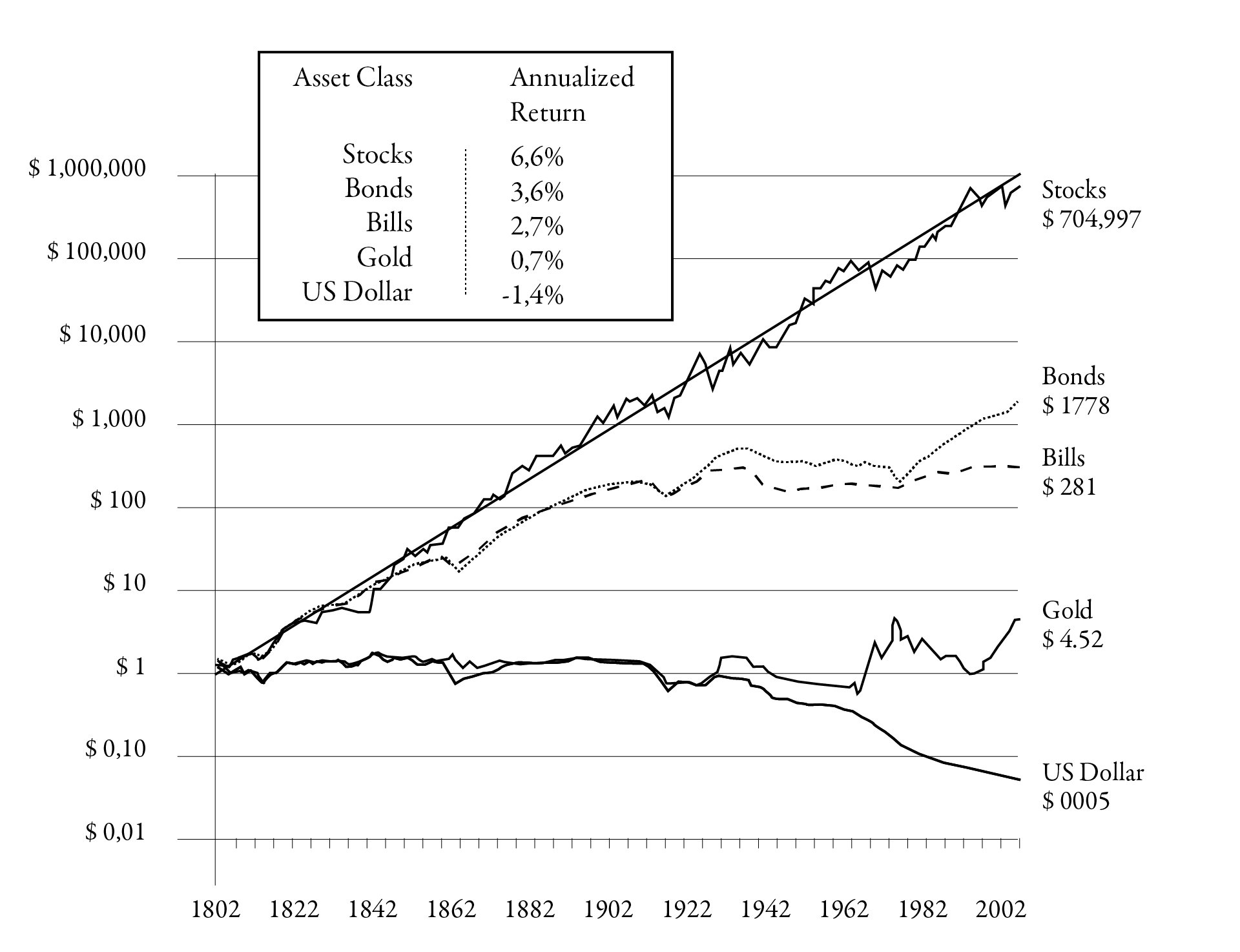

Below is a graph that is very important to me, taken from Professor Jeremy Siegel’s book .Stocks for the Long Run.The data shown illustrate the performance of major asset classes from 1802 to 2002, helping to dispel some myths.

Total Real Return on U.S. Stocks, Bonds, Gold, and Dollar, 1802-2012

Ten years ago, when I began my journey as an investor, interest rates were consistently close to zero. I grew up with “Aunt TINA” (There Is No Alternative) Alternative). In this specific case, bond rates were so low that it wasn’t worth holding bonds, and equities were the only investment that made sense from a practical point of view.

Today, I still haven’t bought a bond, and I’m not sure if I ever will. Maybe “Aunt TINA” has altered my risk tolerance. In reality, I believe my decision depends primarily on two factors: time horizon and portfolio volatility. Currently, my time horizon is very long, and my portfolio’s volatility is below 20%. For now, that suits me fine. Moreover, the cash in my Interactive Brokers account is earning a 4.8% yield.

Bonds and Interest Rates

Generally speaking, high interest rates present attractive opportunities for investors.

For example, the most important bond on the market is the U.S. 10-Year Treasury (10Y T-Note). As I write this article, the yield is 4.24%. You might be wondering how it’s possible that it yields less than cash in Interactive Brokers. This phenomenon is due to the inverted yield curve, which occurs when the difference between the 10-year and 2-year yields is negative.

A 4% yield presents two possible scenarios: collecting the interest payments or gaining capital appreciation by selling when rates fall and bond prices rise. Since the interest rate is in the denominator of the price formula, the lower the rate, the higher the price.

We all know that rates will have to come down because inflation must return below 2%—that’s the Fed’s goal. But no one has a crystal ball to predict when.

When investing in bonds, it is crucial to understand the concept of duration, which measures the bond’s sensitivity to interest rates and, consequently, its volatility.

The longer the duration, the more you’ll lose when rates rise and the more you’ll gain when they fall

In general, a bond with a duration of five will lose 2.5% in price if rates rise by 50 basis points, while another bond with a duration of twenty-five will lose 50% if rates rise by 1%.

Buying a Bond ETF or Individual Bonds?

For the small investor, often referred to as retail, it is much more practical to buy an ETF because there are often minimum purchase amounts for individual bonds, which would complicate portfolio construction. With ETFs, you can easily diversify both in terms of duration and type of issuer (sovereign, corporate, etc.).

If you’re considering adding bonds to your portfolio or already have them, you will need to rebalance annually to maintain the percentages established during planning.

Rebalancing is counterintuitive because it pushes you to sell the component that has risen and buy what has fallen. In finance, there’s a fundamental law called regression to the mean.

If you think this kind of reasoning is starting to become too complicated, there are robo-advisors that can do it for you. Recently, Vanguard launched a new ETF called Life Strategy. These instruments generally do a decent job, and the benefit outweighs the cost of potential human errors, especially for beginners.

In Conclusion

By adding a portion of fixed income, you will reduce the volatility of your portfolio. Diversification, perhaps, is the only free lunch in finance.

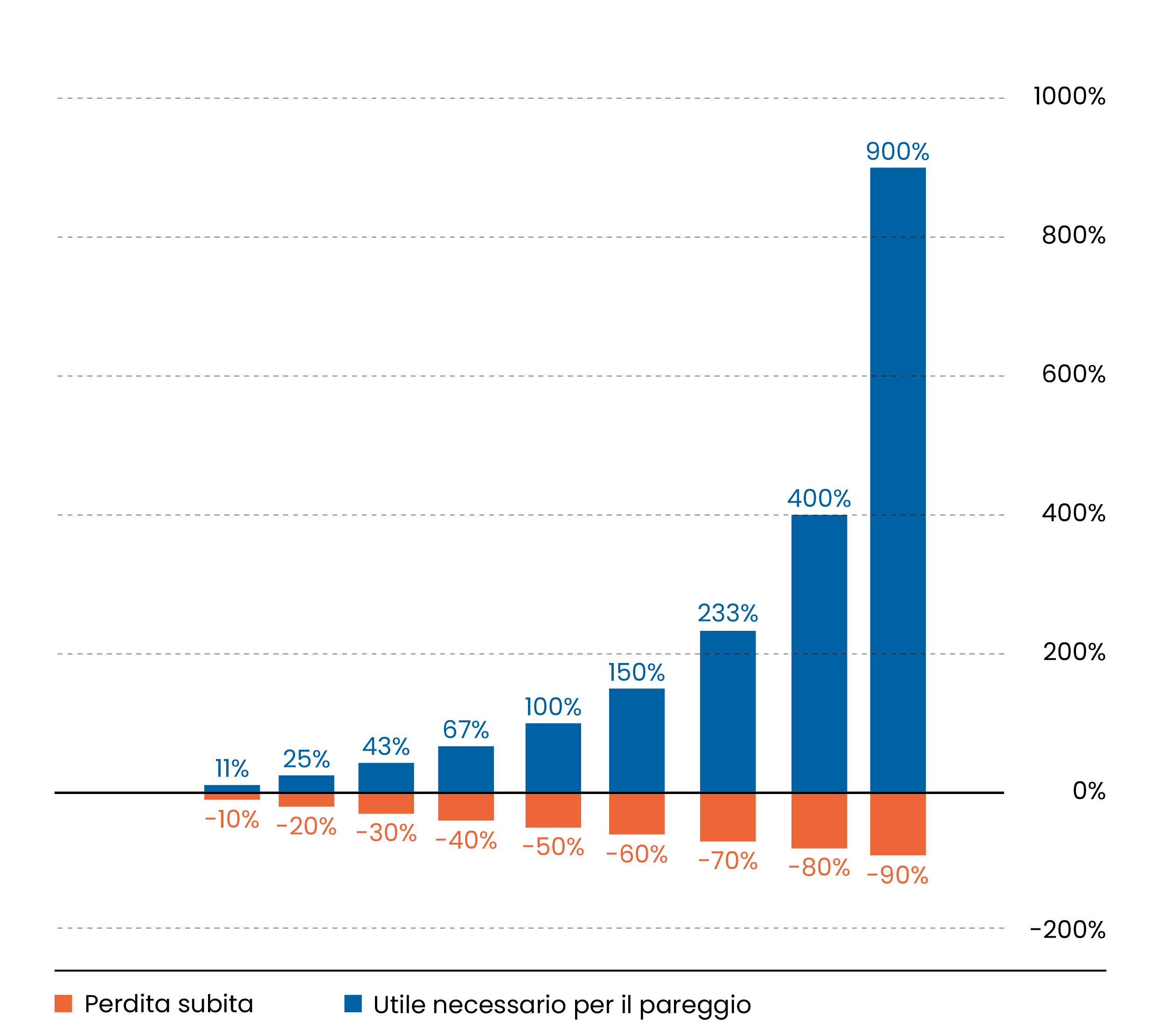

Reducing the volatility of your portfolio below 20%, with bonds or cash, is crucial. It’s possible to recover equity losses in a relatively short time, but only to a certain extent.

Use bond ETFs and don’t forget to rebalance your portfolio annually.

On avance!