Do you think the journey to financial independence ends once you reach your desired sum? The answer is NO, because the most difficult part is the descent.

Mount Everest is the highest peak on Earth, with an altitude of 8,848 meters. The first expedition to reach the summit was that of Edmund Hillary and the Sherpa Tenzing Norgay in 1953. It was an achievement many deemed impossible, and Queen Elizabeth knighted Edmund Hillary, making him “Sir” for his extraordinary feat. In truth, the first person to reach the summit was George Mallory in 1924, nearly thirty years earlier.

But if George Mallory reached the summit of Everest in 1924, why did all the fame go to Edmund Hillary?

Because the latter not only reached the summit, but also descended the mountain. Mallory wasn’t as fortunate. Like most who have perished on Everest, it was the descent that proved fatal.

With this brief story, I want to tell you that the journey to financial independence doesn’t end once you’ve reached the projected sum.

The hardest part is the descent

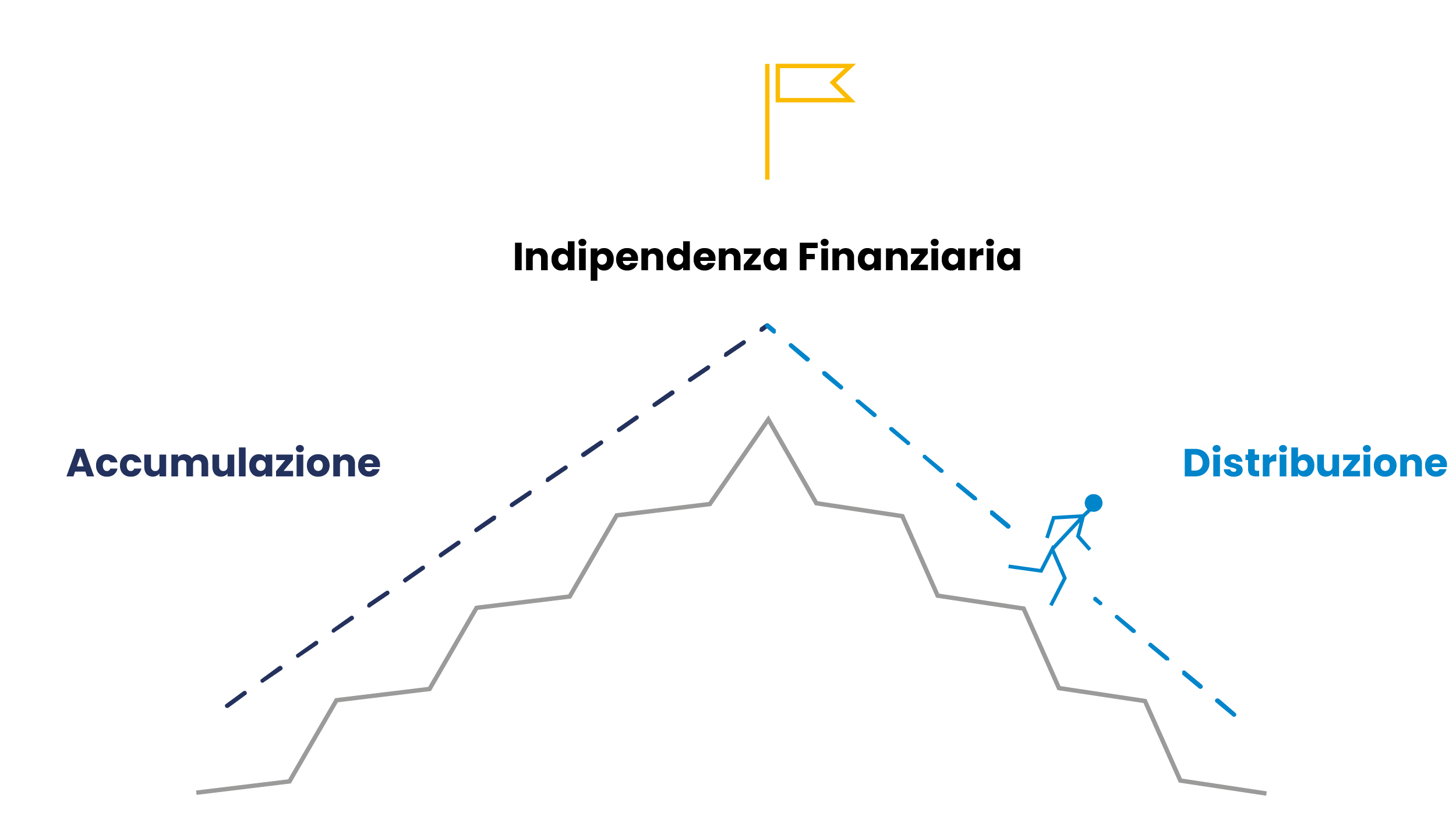

The Distribution Phase: The Descent

The descent is the second phase, known as the distribution phase, in which you must protect your capital to continue receiving its benefits perpetually. You must apply the same principle as the goose that lays the golden eggs. The goose (capital) must not be overburdened by demanding more eggs (high withdrawal rates) to ensure it continues producing golden eggs (interest) perpetually.

The Dilemma: Probability-Based vs. Safety-First

As with all things in personal finance, there is no single rule to follow. In my opinion, there are two different reference models that can be applied. The main difference between the two is the trade-off between the risk-return of an equity portfolio and the protection provided by insurance products and/or bonds with guaranteed returns.

Personally, I believe that a probability of success above 90% is a good starting point, although small adjustments may be necessary along the way. I chose the probability-based approach, but if a 10% risk is a concern for you, then you should lean toward the safety-first philosophy. Remember, there are no free lunches in finance, and safety comes at a cost. If you want to delve deeper into this topic, I recommend reading Wade Pfau‘s articles or his book How Much Can I Spend in Retirement?

Does the 4% Rule Really Work?

With that said, let’s get to the heart of the matter. In 1994, William Bengen, in his article Determining withdrawal rates using historical data, created a stir in the financial community, particularly among financial planners, by introducing the 4% rule.

This number represents the withdrawal rate, SAFEMAX, adjusted annually for inflation, that should allow you to preserve your capital for thirty years. In 1998, Bengen’s work was supplemented by the Trinity Study which added more data and different strategies. The rule caused a stir because, before then, the financial community believed that a higher percentage of capital could be withdrawn.

Application Example of the Rule

Here’s a concrete example: if you’ve reached a capital of $ 1,000,000 properly invested in the financial markets with equity ETFs, in theory, you can withdraw up to 4% each year, meaning $ 40,000 ($1,000,000 x 4%), without significant risk of depleting your capital in the short term—it should last at least thirty years.

Withdrawals can be made in various ways depending on the financial instruments that make up your capital. If you use accumulation products, the operation will be carried out by periodically selling shares, whereas if you use distribution products, you’ll collect dividends without reinvesting them. It depends on your asset allocation.

Personally, I don’t believe there’s a single rule that applies for navigating thirty years of financial markets. The matter is too complex to be summarized this way. Needless to say, over the next thirty years, we will change, our approach to life will change, and our risk tolerance will evolve. To survive, you must be Darwinian and able to adapt to change.

I have been using the 4% rule, with common sense, for almost three years. My descent, or the distribution phase, has just begun, and for now, I have set the with

The Sequence of Returns

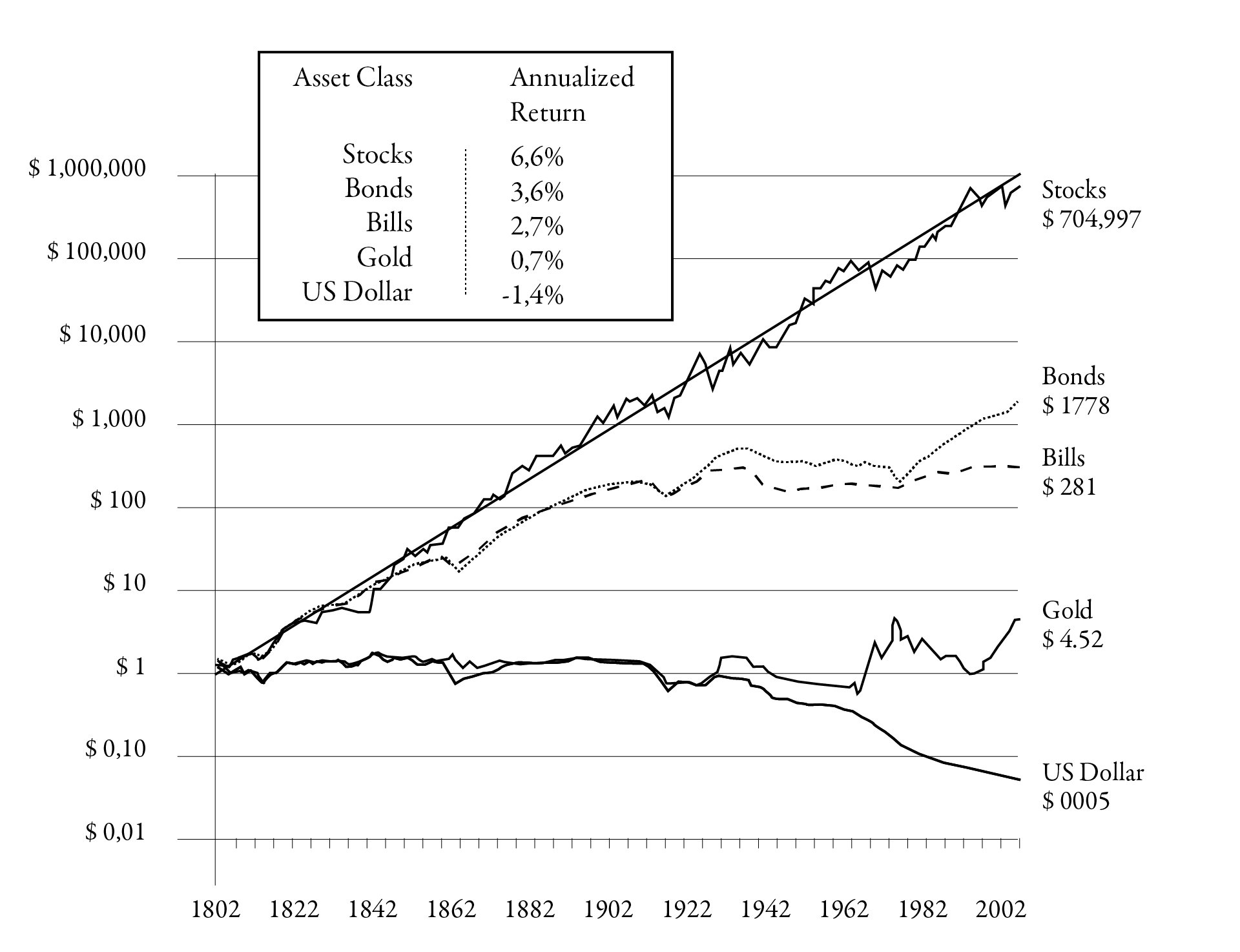

The first major issue, which unfortunately we can’t control, is the sequence of returns. Thanks to Jeremy Siegel, author of the investment classic Stocks for the Long Run, we know that since 1802, the real return on stocks—meaning the net return after accounting for inflation—has averaged 6.6% annually.

Bonds have had an annualized return of 3.6% over the same period. You might be surprised to learn that gold has only registered a 0.7% return, also in real terms, and of course, cash has yielded a negative return in this respect. Holding money in a bank account, liquidity funds, or savings accounts would have preserved nominal capital but not protected it from the slow erosion caused by inflation.

The big problem is that the returns described above are averages, but in reality, markets are extremely volatile and unpredictable, especially in the short term. The sequence of returns has a huge impact during the early years of the distribution phase when your capital will be at its highest value.

If you enter a period of “bonanza,” then 4% will be more than enough, and you may even be able to increase it so as not to risk, as they say, being the richest person in the graveyard. On the other hand, if markets perform poorly in the early years, it’s likely that some adjustments will be needed, as your funds could deplete significantly or, at the very least, may not last throughout your life.

Flexibility During the Descent

At the start of your journey, you need to have some flexibility; remember, you’re still young because you’re in early retirement. In my view, there are two main options available.

The first is to reduce the withdrawal rate for a period, lowering it by about one percentage point. If you can’t reduce or defer some expenses, the second option is to take on small projects to bridge the gap. These should be stimulating projects with people you admire.

Finally, don’t forget that most studies are based on the American market and refer to a time when interest rates were higher. The data pertains to U.S. stocks and Treasuries and is, therefore, expressed in dollars. Additionally, the withdrawal rate doesn’t take taxes into account.

Given the current economic situation and for someone who isn’t American, I believe it’s more appropriate to use a slightly lower withdrawal rate, around 3.5%, at least in the early years.

The first years are the most important, even from a psychological perspective. Initially, you’ll feel disoriented and will need to change many of your old habits, but over time, everything will get better, and you’ll be much happier. Try not to take unnecessary risks after so many years of sacrifices, and remember that you need to descend the mountain safely, avoiding any missteps along the way.

Final Thoughts

In summary, the journey to financial independence doesn’t end once you reach your desired capital. The distribution phase requires careful attention and strategy to preserve your capital and ensure a stable income over time. The 4% rule is a good starting point, but flexibility and adaptability to market changes are crucial. Careful and mindful capital management is essential to ensure a safe and peaceful descent, just like coming down from Everest after reaching the summit.

On avance!